I honestly don’t remember when or why I first heard Bob Mould’s 1989 solo album Workbook. I’d never listened to much of his former band Husker Dü; I think that at the time I was just into somewhat more ethereal and melodic (and usually subtly or not-so-subtly subversive) indie music, most of which I’d been exposed to by spending pretty much any free night I had in the back room of Hoboken’s justifiably revered Maxwell’s, where anyone who was anyone on the indie music scene (Nirvana, Soundgarden, The Replacements, the Bongos, Richard Lloyd, etc., etc.) came to play in the late 1980’s. The Feelies (and their various permutations) were the epitome of the kind of (ethereal, melodic, subversive) bands I loved at the time, and I did my best to show up any time they played there.

Back to Workbook, which Mould released shortly after an apparently acrimonious breakup with Husker Du. The songs were a major departure for Mould–atmospheric and melancholy, with touches of bitterness and regret, stunning guitars, and fascinating lyrics (it turns out that the Feelies’ drummer, Anton Fier, played on the album, so there’s that). It’s one of those albums from which I can never quite decide which song is my favorite, because I love them all (although if I were forced to name two, they’d be “Sinners and Their Repentances” and “Poison Years”–I think).

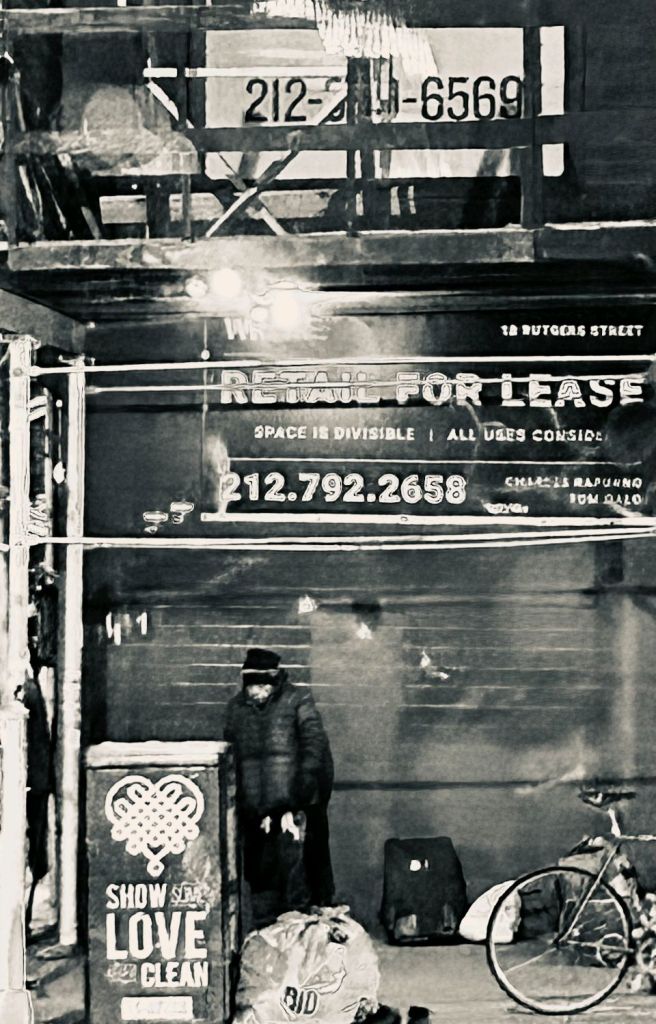

Two memories always flash into my mind when I think of Workbook. One is of standing on the subway platform waiting for the A train and suddenly feeling a wave of gratitude that the album existed and could accompany me as I traveled around Manhattan to visit clients in their homes or at various city hospitals. (Starting in the fall of 1988, I was a caseworker for people with AIDS for NYC’s Department of Health. At the time, people who were diagnosed with full-blown AIDS usually had only a few months to live, the only medication available at the time being the toxic and pretty much useless AZT. I learned to love and grieve people within very short periods of time back then, and most of the people I cared about most were gay and/or heroin addicts.)

I’ve always assumed that, as a gay man and recovering addict, at least some of Mould’s angry and sorrowful lyrics were likely influenced by those terrible days, although I can’t speak for him with any certainty. But lyrics like these from “Sinners and Their Repentances” certainly resonated with me at the time, when the “AIDS world” had become my world, and most other things going on at the time seemed irrelevant:

All these things I’ve done before/It doesn’t matter any more.

Or, from “Lonely Afternoon”:

It’s the slivers flowing through my veins/It’s a sign that I’m alive./You’re lucky, oh my friend, so lucky/You’re lucky just to be alive.

And from the same song:

Life can be so cruel/And the ones who make decisions for you/Well, they better understand.

I may be simply projecting some of my own feelings from that time onto lyrics by which Mould was referring to other things, but of course that’s part of the magic of music–a single song can mean so many different things to different people, and almost any interpretation is valid if it resonates with the listener.

The second memory that also comes to mind when I think about Workbook is even more simple–it’s the end of my work-day at the Division of AIDS Services, and I’m walking up West 14th Street toward the train that will take me home for the night. I’m listening to my Walkman (yeah, Walkman) as I go. The early-evening light is the warm golden-pink that makes Manhattan look even more beautiful to me than usual. Perhaps that day I’d managed to get a homeless person with AIDS into an SRO hotel or apartment, or perhaps I’d screwed up on paperwork again at the office, or perhaps I’d lost one or more of my thirty-or-so clients yet again. Maybe it’s not even Workbook that I’m listening to just then, although there’s a very good chance that it is, having become an album that seemed to capture that strange, heartbreaking, and occasionally beautiful time when love and grief, and a comradeship with so many people who were considered outcasts, and embody the light in which my own life had become bathed.

Nancy Bevilaqua.

Nancy Bevilaqua is a writer (mostly poetry) who was born in Manhattan and now lives just across the Hudson River from it in the wonderful town of Hoboken, NJ. In the late 1980’s/early 1990’s she worked as a caseworker/counselor for people with AIDS and the homeless (she published a memoir entitled Holding Breath: A Memoir of AIDS’ Wildfire Days about that time in 2012).

She has also “worked” (if one can call it that!) as a travel writer, and her articles were published in National Geographic Traveler, Coastal Living, and several newspapers and in-flight magazines.

These days, she’s finally learning to play drums, having taken her first lesson at age 61–nearly 50 years after hearing Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir” on the radio and deciding that she wanted to be a drummer–and continues to write poetry and do some photography. She also plays a little guitar. Very little.

Her son, Sandro Bevilaqua, is a talented musician and producer who also lives in Hoboken and plays at various venues around NYC. The fact that he grew up to be a musician makes her incredibly happy. (His debut EP, Lila, is available on all the usual platforms, and just happens to be one of Nancy’s all-time favorite albums.)

Nancy lives with her angelic, weirdly intelligent, and occasionally maniacal Pit/Boxer mix, Naima (named after John Coltrane’s first wife). She is not a musician, although her vocals can be pretty loud.”

All photos and writing are provided by Nancy, if you’d like to read more of her stuff, click here 👉 https://wordpress.com/view/nancybevilaqua1.com

Leave a reply to aleathiadrehmer Cancel reply